Jaenine Parkinson talks to Andrew Pelling about two collaborative art works that bridge art and science, which he was involved in presenting at the Open Ottawa Libra conference held at Arts Court on Wednesday September 28, 2011. Andrew Pelling is Canada Research Chair and Assistant Professor in the Departments of Physics and Biology at University of Ottawa. He heads up Pelling Labs, a laboratory for Biophysical Manipulation, housed in the University’s new Center for Interdisciplinary Nano-physics.

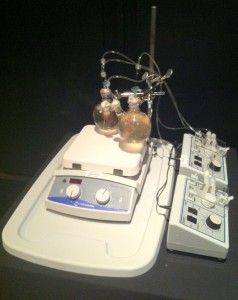

Andrew Pelling and Daniel Modulevsky Organ Re-Purposing Bioreactors (2011)

Jaenine Parkinson: Could you explain to me exactly what was going on in the two pieces you had at Open Ottawa Libre? Maybe we can start with the tissue culture piece, that you made with your student Dan Modulevsky? From what I gathered, it looked like, there were two bits of steak? And you were, someone said, sucking the cells out of them?

Andrew Pelling: Yes, we were extracting the cells out to leave behind what we call an extra-cellular matrix. It’s like a scaffold that cells grow on, it’s made out of collagen—a protein. There are cells in tissue that make the collagen and then there are other cells that make muscle and nerves, and things like that. We have been developing this process to remove all the cells and just leave behind the matrix. Which is great because, one, for a practical reason, to make the matrix in a lab is unbelievably expensive.

Andrew Pelling and Daniel Modulevsky Organ Re-Purposing Bioreactors, detail

JP: Oh, it seems like a highly detailed process; so you can actually synthesize it?

AP: You can, absolutely, but it is incredibly expensive. I’m not sure why. It’s not actually very hard. I don’t know what it is that makes it so costly. There are a lot of proprietary products out there you can just buy to synthesize it from pure collagen. But, for what ever reason it is very expensive; to make a large piece.

Decellularized steak

JP: So it’s use is primarily for recreating new tissue, with different cells in it?

AP: It is part of a huge push called regenerative medicine. Because you can take stem cells and coax them into being anything, like heart cells. But then you’ve just got a blob of heart cells and you need a structure. One way to build that would be to make it artificially, to create these collagen scaffolds in the shape of a heart, and put your cells onto it. That’s one approach and it is expensive. But it is very controlled. So, a few years ago a group took some hearts and got rid of the cells (decellularization) and there you have this scaffold of a heart. Of course, now you have to kill one animal to make a heart to put into another animal, so I’m not sure if it really makes much sense. It is also not very interesting to me personally, it’s kind of a standard thing that can do with this technology.

What we got interested in started with the little bit of animal work that’s going on here. In many cases you will study one part, in our case we were studying the aorta and heart disease, but the rest of the animal gets tossed, and it is quite wasteful I think. So I started thinking, well what else can we do to get more value out of this life that we have just ended? I just felt very guilty about that whole thing. And we started thinking about what about hacking the organs that are in there. Sort of bio-hacking.

JP: When you use the term bio-hacking what do you mean?

AP: Very much like you would in technology where you hack a piece of technology to repurpose it, use it for unintended purposes. So like Protype D with their printers. So, I thought, why can’t we do that with these organs? Can we take muscle and get rid of the cells and create an new structure that doesn’t currently exist in nature? Can we create little pumps that join to little arms and start putting them together to make monstrosities or tools and devices that would be bio-compatible? It is just something nobody is doing, so it just really attracts me. It’s so weird, but we have the technology. It is so, easy to get rid of cells and put whatever cell we want in. So, we can take a heart and put kidney cells into it; so it’s this heart-kidney. You just need a couple of electrodes to make it pump. You could exploit some of the biology of these kidney cells, to, say, pump and filter at the same time, or who knows. We do a lot of work with micro-fluidics and micro, miniaturized technologies. We spend a lot of times making these things synthetically, well could we make them organically? Then if it is all biological it will be easier to put into something as a device, rather than a new organ.

JP: And always the ethics comes up…

AP: Absolutely.

JP: What is it like working within the University framework? What sort of controls do they have in place around this type of work?

AP: Yes the University has good ethical guidelines, especially in terms of how you handle an animal, or bio-hazardous stuff. But, a lot of our work doesn’t actually involve animals. There are things called cell-lines which are immortalized cells. That just grow, and grow and grow and grow and don’t need a lot.

JP: I was reading your blog, plasticbiology.net there is one from a cervical cancer victim who died in 1951.

AP: That’s a really famous one: HeLa.

JP: It seems bizarre to me that this woman, Henrietta Lacks, died from a horrible disease, in 1951, and a part of her is still living. It is kind of amazing and horrifying at the same time…

AP: It is completely crazy when you sit down and really think about it. There is more of her biomass now then there ever was. Every lab in the world has HeLa cells. I’m sure this has been thought about by other people, but it is such a bizarre phenomenon. What’s even more strange is that it is so easy to genetically modify these things. To create new cells that would have never have existed. It’s bizarre how much power we have.

JP: Then there is this sort of fear/fascination blend to it, and many people just don’t want to go there because we don’t have the ethics yet to deal with it.

AP: Well, there are a tremendous amount of ethical guidelines. You have to get certified to do animal work and there are rules and regulations to minimize suffering. Although, it is interesting, because Canada does things a lot differently from the UK, where I used to work. I think maybe North Americans are a bit more squeamish. Some of the rules that are in place aren’t actually better for the animal, I think, but they just don’t look as horrific.

JP: But do ethics come into it when you are thinking about these projects?

AP: I’m not an ethicist, I think there are big issues there and sometimes I purposefully say stuff just to provoke ethical questions.

JP: I suppose half the attraction is to play with that boundary line?

AP: Absolutely, that is definitely part of what interests me, is that pushing, always. But, at the same time, I would have a really hard time growing mice for the sole purpose of bio-hacking. We have these mice already, and what we are working on is a collaboration with a medic who has discovered a protein that minimizes, and maybe, perhaps could cure heart disease. Interestingly, during a recent discussion, I came across Sports Casting’s list of ethical debates in sports science, which got me thinking more deeply about the implications of our work. So, there is real reason to do this work, and there is real merit behind it. And what really bothered me at the end is this ethical thing—we have this entire mouse, minus a heart, that’s just getting incinerated. There must be something we can do with this.

JP: Is this where the science stops and the art kicks in? Because, you don’t have an artistic background, do you?

AP: Well I did go to an art school when I was younger, and that’s where I learnt to love math. Some people get confused by me sometimes, some people call me an artist, some people call me a scientist. I like to think of it more as just being a creative person. And I don’t think there actually is much of a difference. I think it is more a medium you work in.

JP: Except with science there is more of a focus on purpose, where as exploration is more the purpose in art.

AP: In science there is more of a push for technologies, applications and profit. I like to keep my lab more in the field of pure exploration, curiosity driven. But it is getting harder. Although there are still grants for that – my main operating grant is called the Discovery Grant – its mainly for that fundamental research. It’s a federal grant, most science Professors have access to it. Although, I like to push those boundaries a little further than most. The Discovery Grant is much more open ended, but pot of money is much smaller than with industrial grants.

JP: So where are you going to next with this tissue culture project?

AP: The work we are doing with decellularization is a slightly different twist on regenerative medicine, where it’s not so much about making transplant products, but about making devices and things you can use. Integrating them with micro-fluidics or biosensors, or who knows. We can either spend years and years developing our own mechanical or micro-mechanical device that pumps or we can use something that already there. These aren’t trivial issues, but this is another way of thinking. Specifically, it’s not a way not many people are looking at right now, and that is why it is interesting. It’s more just stepping into the dark and seeing what happens.

Andrew Pelling and Donna Legault Darkfields (2011)

JP: So the work that you did with artist Donna Legault, that is completely different.

AP: Yeah, that was interesting, because we just got shoved in a room and we didn’t even know each other.

JP: Oh, how did that happen?

AP: Julie DuPont, who is the Cultural Planner for the City of Ottawa, was organizing Open Ottawa Libra and she arranged a meeting between a few of us at PrototypeD. We were just going to see their space. We ended up talking about Open Ottawa and some themes for it and all of a sudden we were planning a whole bunch of stuff for this event. Donna and I met there I guess because one of my previous art-sci things was this cell sounds project and we were just introducing ourselves and I talked about that. Then it turns out she is a sound artist, so there was this connection. We came up with some crazy ideas about using sound to manipulate cells. I don’t know if any of that will ever turn into something. But she came to the lab one weekend and we tried a few things out. She has these base shakers, and she has been working with infra-sound, low frequency sound, feeling and visualizing sound. We put some beakers on top of these base shakers, which vibrate to create little standing waves. It became about visualizing sound with water. The other consideration was capturing the waves, you actually have to have the lights at a certain angle, to scatter up into the camera. We were making sound visible, but also making these waves visible.

Andrew Pelling and Donna Legault Darkfields, detail

JP: So could you explain a little about the cell-sound work you had done previously?

AP: That was called Dark Side of the Cell (2004) www.darksideofcell.info and that was with an artist I have been working with for years Anne Niemetz She and I met in UCLA, we were both graduates. Our advisors were organizing this huge art-sci exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) which was this year long, 10,000 square foot exhibition about the interface between nanoscience and art. Since I was working on these cell sounds and she is a sound artist, our advisors kind of pushed us together and asked us to do the sound design for the whole exhibit. Again, we started talking, and she was doing an MFA so we developed this piece called Dark Side of the Cell. I was using this device called an atomic force microscope. It is sort of like a record player needle on the end of an arm, you can use it to image atoms and image cells. So I was using it to feel how cells move. Which was, at the time, completely bizarre stuff to do in the field. And I discovered in particular yeast cells these small low amplitude oscillations in the cell wall; high frequency, about a thousand kilohertz. They were very transient, they would come and go. The digital data looks like sound waves, like a .wav file. That inspired my advisor and I to convert this to sound, so we could listen to these cells. So I had that going, then I met Anne and we developed this Dark Side of the Cell installation. Which is a concert of pure cell audio, untouched, unaltered, just the volume has been changed, and we organised it into themes, for this immersive sound environment. We had big cell sculptures and projected onto them images of the cells you are actually listening to. The show got a surprising amount of press, and Anne and I have been working ever since on different things. It’s a little harder now that she is in New Zealand.

Andrew Pelling and Anne Niemetz Dark Side of the Cell (2004) installation detail

JP: Didn’t you met up with her recently in Perth?

AP: Yes, she and I went to SymbioticA, which is this bio art center in Western Australia. I’ve known Oran Catts and Ionat Zurr from the Tissue Culture and Art Project for a while now. That trip inspired my Lego project. I did it in preparation for going out there. Again it was triggered by a feeling of guilt. When you work in a lab as a student you don’t really think about where a lot of the things come from, or are wasted. But when you are the guy running the lab and buying these materials you see that there is a tremendous amount of waste – and plastic – bio materials and animals. We have a culture of mass production and we have a huge mechanism in our society for it. And none of it its recycled, it’s all incinerated, because you are worried about biohazards. And these are legitimate concerns. But there is a huge amount of waste, and it doesn’t really get talked about. So I thought, why don’t I think of a way to push a debate. Not necessarily to answer any questions, but just to bring it to the front. And that was the Lego project. It is this idea that even living things are plastic in our lab. We can totally manipulate them; get them to do whatever we want.

Andrew Pelling Semi-Living LEGO Minifigs (2011)

JP: And cells are like these little Lego building blocks anyway.

AP: Exactly, so I took these HeLa cells and inserted a jellyfish gene – again, because I could – to make it glow. So you have this human-jellyfish organism now. It’s just this Frankenstein. But again, you just buy the products off the shelf, it’s all plastic, you don’t have to do anything special, I could teach anybody to do it in an hour. It is kind of scary. We do it every day. It is just this tool we use. And then I thought, how can I represent it – and Lego figures were the answer.

JP: It also brings it a bit closer to home, turning this jelly-like blob into a skin, and referencing the fact that there are human cells being used. Because that is the scariest thing, for many, because not only can you change our food and animals, but you can change us as well.

AP: Of course, in reality, could we do it to a human? Probably. It would be a lot harder, probably. But conceptually it is all there.

JP: And then there is the whole ‘slippery slope’ argument. If you take one step, why not take the second and third.

AP: And it is all commercially available. If you have enough money you can do it. Anyone can do it. Especially with that whole DIY bio thing right now.

Andrew Pelling Semi-Living LEGO Minifigs, detail

JP: So did you present your Lego work at SymboticA?

AP: I showed some pictures and just discussed it. Of course, at SymboticA these are issues they have discussed at length, because that is what they think about all the time.

JP: Did you see anything interesting while you were there? What other problems were people considering?

AP: Well the other aspect of our work is that we try and build mechanical devices to manipulate cells. Stretch them and pull them and poke them, to see what happens. And what shocked me was when I showed up at SymboticA one of there students was building exactly what we were in the middle of building and he had done it ten times better than us actually. It was amazing, here are a bunch of artists building the same device for the same purposes. It was so strange. Our project came from our work with the heart. If you think about the aorta it is constantly expanding when your heart pumps, there is a pressure on the veins and arteries, and they expand. So the cells in those walls are being stretched and compressed and undergo different types of stress and strain.

JP: And you just wanted to see what the upper threshold is?

AP: I just really wanted to image, video record, how they respond. It is amazing, these are just such simple perturbations but when we look at the data carefully the responses are unbelievably complex. We are sort of at a stage where we don’t even have enough physics to describe what is going on there. We don’t have the models. We have some models that sort of work, but what we are finding again and again is that when biology does these things, these physical things, it doesn’t behave the way we expect it to. And you would never have discovered that if you weren’t really looking. For many years people weren’t looking and they derived a lot of physical equations that are very elegant. But they have no basis in describing a real cell. That is why we just look.

For eons science has just been about understanding how cells work in normal environments and circumstances. There are still a lot of questions to be answered, and a lot of knowledge there. But what has been interesting me much more now is what happens when we put them in very extreme conditions that have nothing to do with normality or make completely new types of cells and new types of ‘organs’. Let’s attach a lung to, I don’t know, a piece of steak, and see what happens.

JP: Yeah, I remember Stelarc grew an ear on the back of a mouse and it was really controversial.

AP: That is really part of the inspiration. Along with Steve Mann in Toronto with his electronic surveillance and integration between bodies and electronics. So could we start pushing our science away from just try to understand how things normally behave. What I am more interested in now is how they behave under really extreme, artificial conditions. Which is really interesting, especially if the future is this integration between technology and biology. I bet there are a lot of responses, the potential of cells, that we don’t even know exist.

JP: Do you think you would be doing this type of work if you didn’t have access to all your equipment?

AP: Well that is what is so cool about the DIY bio movement. In a lab a company could sell us a piece of equipment for say, $12000-15000 dollars, but it is really a couple of hundred dollars worth of parts. We have built our own equipment out of garbage and some of it is even more accurate than what we have bought. So you could do it. The general public can do it. For instance, our centrifuge, would cost $10,000, and I just read an article the other day of someone constructing one from a salad spinner and a drill.

JP: What about opening up these labs for other artists to come and work in? Does that happen?

AP: It does, Anne Niemetz has worked here, twice now. And I am hoping Oran Catts and Ionat Zurr will come over sometime as a residency. There is no formal mechanism but everything we are doing is so in the middle of art and science anyway, it all fits. So really all you need is some safety training.

What we are working on in the lab at the moment is miniaturization, to create micro-fluidic devices. We have developed one to stretch cells using vacuum. When we apply a vacuum to one of the chambers they shrink, and that allows us to pull on the cells. And each is individually controlled. We are experimenting a lot with this type of silicone technology, because we can integrate electrodes.

The other project we are working on uses two lasers, that we point at each other. Then we have a fluidic channel that a cell floats down. And when it hits these two lasers, the lasers can hold it. So very Star-trec, tractor beam. Then by manipulating the power of the laser we can start stretching the cell. I don’t know exactly what we are going to do with this. But it is amazing to see that it is possible. The idea that we are toying with is that if you manipulate these cells, is to find out if you stretch a lot of cells and collect them afterwards, and grow them will they grow differently? If we do that with stem cells, do we get a different response? We will see, I guess.

We are also working with micro tumors that will grow in chambers of these micro-fluidic devices, so we can study how they behave under different mechanical situations. Because, when cancer is spread the first thing that forms is these micro-tumors, a tiny collection cells. And they are very sensitive to the mechanics of their environment. But exactly how, and what is going on and why, we don’t know. This is one way we can study them.

Usually how I develop a new project is that I just have some image in my head of a cell in a particular environment. I have no idea why it is there, or how it got there. But, let’s make this! Let’s just figure out how to do this. It doesn’t ever start with a particular question or scientific hypothesis.

JP: There seems to be dove-tailing end-goals here. What you are doing could have some application to medical science or it could be…

AP: Complete madness. Well I’m not a medic and I don’t like to say my research is about advancing medicine, because I have no business talking about medicine. A lot of scientists do this because it helps them get funding. But really have no business talking about medicine.

JP: But a lot of medicine is just an elaborate, educated guessing game.

AP: Absolutely, I have always said, we will develop the concepts and it is up to the medics to develop the applications. And actually decide if my findings do have applications or not.

JP: So do you have any presentations of your work coming up?

AP: I’m giving a bio-hacking talk at Concordia, Montreal on 1 November, which is open to the public. I don’t know if you know Tagny Duff, she is an artist and she had a residency at SimbioticA and I think she has almost got her own tissue culture lab set up there. Called, Fluxmedia, I think. It is a centre for bio-art and bio-ethics. Show some videos, of how cells move, which is quite incredible.

We use a silicone mould stamps, and the cells grow around it. When we pull it out we are left with a shape. We are studying how they fill that space back in. These angle of the mould has such huge effect on the rate, and which cells start moving and when and how they are communicating. It is called wound healing. The traditional paradigm for this is you make a line, a scratch, and you’d time how long it takes for the cells to heal. I thought, well what happens if you make two scratches? What happens if you start changing the angle here? What we see is there is a collective behavior going on here. The cells at the edges move as a unit. Depending on how steep we make the angle, we get different dynamics. If we make a really steep cut some cells don’t move and others do all the work. How that is happening and how they are communicating isn’t really clear.

JP: It is amazing, because this would happen in your body too?

AP: Yes, especially if you got cut. For fifty years people would just make a straight line, it was just never questioned. But there is anecdotal evidence of surgeons making jagged, zigzag cuts and them healing better. I came up with this idea because I was talking with two of my students suggesting that they try it. And just even convincing them to do it was so hard. Because, why would you want to do it? It is always done with a line, so we have to do it with a line. Why would we do it any other way?

JP: To see what happens.

AP: Just shift your mindset.

Tags: Andrew Pelling, Anne Niemetz, Bioart, Daniel Modulevsky, Donna Legault

Details about Pelling’s upcoming talk here: http://fluxmedia.concordia.ca/events/

The ear on the back of the mouse always bothered me. Because no one ever says whether it hurt