Excerpt from “The Van Gogh-st in the Shell” by Diana Stephens.

Edited and adapted especially for the Artengine blog by the authoress.

HELLO WORLD

In the current age of technological progress, many of the die-hard humanists retreat from the world of glowing rectangles and LED lights into the realm of artistic expression. Science-fiction has—since the 19th Century, at least—been casting a wary eye towards the innocuous machines that we use to better build our societies, but by looking at paintings and other such artistic works of art, these humanists can comfort themselves in their knowledge that as long as the human soul can create art, we have not yet become obsolete.

Yet even in the safe havens of museums and galleries, an intriguing revolution is quietly taking place. As the humanists admire a colourful painting of a bearded gentleman on a blue background, a creeping doubt sets in as they read the placard beside it:

Theo, 1992

Painted by AARON

AARON, they learn, perhaps with a sense of growing unease, is not human; it is a robot.

AARON is the brainchild of Professor Harold Cohen, an artist in his own right and one of the scholars at the Slade School for Fine Arts in London, England. His direction in art changed considerably in 1968 while being a Visiting Professor for the University of California, San Diego where he got his first taste of computing. What followed was initially more of a thought experiment than the philosophical springboard it would turn out to be.

Trying to solve the question posed to himself—“what would be the minimum condition under which a set of marks may function as an image?”—Cohen developed a computer program to decide exactly that. While starting off in the realm of abstraction, Cohen then advanced to figuring out what was the most basic instruction he could provide a computer in order for it to produce something that looks (to some form of universal agreement) like a rock? An plant? A person? The process has been described as teaching the program to “[model] the decisions made by an experienced artist — as though [Cohen] were teaching a particularly dense art student”. Pamela McCorduck, who has written a book on the subject entitled AARON’s Code, explains the process:

“It implements various rules for positioning and sizing the figures around the picture plane, and rules for making sure that one object is not drawn on top of another. Once set in operation, the program could draw an infinite number of different drawings with no intervention from Cohen. The computer program itself has rules for determining when each drawing is finished.”

BROTHER GIORGIO’S KANGAROO

The task is harder than many computer scientists would appreciate. Cohen describes the process in his essay “Brother Giorgio’s Kangaroo”, where he explains the difficulty that a monk has in sketching a ‘kangaroo’, something he has never seen, as it is described to him by a friend who has visited Australia. To try it yourself, find a friend, a paper and pen, and do the following:

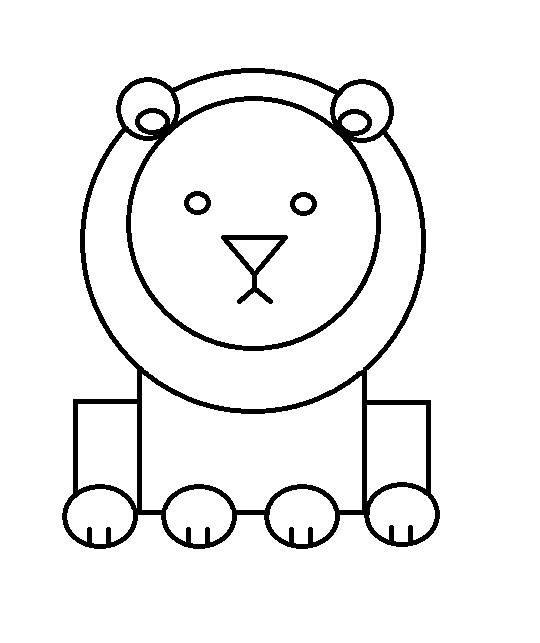

Look at this picture of a lion, made up of simple shapes. Next, without letting your friend see the picture, try to describe it to them and get them to draw it as accurately as possible. However, you cannot use the word “lion” or “foot” itself to describe the image or shapes; only words such as ‘circle’ and ‘line’ or directions like ‘left’ or ‘up’. Your friend cannot ask for clarification. Once you feel you have described the picture well enough, compare the original image with the one your friend has drawn.

Describing the lion is no simple task, but people are much easier to instruct than computers. Depending on your level of descriptive skill, your friend might have even been able to guess that they were drawing a lion; AARON, however, has no concept of what a “lion” is, as it has never seen one. Cohen had to perform a similar task, although his images were increasingly complex; AARON, like the lion, has no intrinsic knowledge about a person’s anatomy or rules about how plants grow.

I, ROBOT

Cohen himself jokes that he would be “the first artist in history to have a posthumous exhibition of new work”. This statement has brought up a fascinating debate amongst artists and computer scientists alike with regards to the artist and their relationship with technology. While Cohen denies that AARON is an art ‘tool’—as his input was the instructions on how to make art, not using it to air his own creations—he also denies that AARON is creative in itself for exactly the same reason; he uses the word “collaboration” to describe the relationship between his program and himself. AARON can only produced images based on the rules taught to it by Cohen, so it will always produce Cohenesque pieces. The question regarding the paintings then becomes: is AARON the artist, or is Cohen?

The trouble that AARON presents in terms of artistry is how one defines creativity—an abstract concept. If AARON is creative, then Cohen has proven that creativity is inherent in the rules of art; that creativity can be taught, rather than exist as a natural talent that certain spiritual and imaginative people have and use. However, if AARON is not creative, can its paintings (for which Cohen provides merely the rules) be said to be art at all, lacking in any inspiration outside of composition?

Any person, when asked to describe attributes of any piece that they find ‘creative’ would use words such as “insight” (seeing something that was not obvious before), “novelty” (fabricating something which is entirely unique), or even some “revolutionary” combination of the two (that is, taking something and adding a personal, unique twist or variation on it). Writer Gerard Beirne quotes Douglas Hofstadter when he claims “that the essence of creativity is pursuing a theme through all its possible outcomes and being clever enough to recognize a bright new possibility with the combinations that emerge. Others have similarly argued that creativity can be explained as a process combining exploration and recognition”. This is arguably something well within the boundaries of what a computer can do.

For many, Cohen’s artistry extends only to AARON’s programming, and insists that each painting of AARON’s is its own. It’s not excessively hard to believe in something like that, particularly if you experience AARON in its full zanelle set-up. A ‘zanelle’, for context, is the word given to a painting by a robot who creates art using non-digital medium of sorts; while there is a commercial version of AARON’s software available for download as a screensaver for any home computer, Cohen’s true AARON robot actually uses a long robotic arm to physically draw each picture and paint it with real paints. While AARON may not be the only zanelle painter out there, he is certainly the first, and—as it was still in operation as of at least 2003—the oldest, having been growing and drawing for about 40 years and being exhibited in many reputable museums and galleries. Its paintings pass the ‘Turing Test’ of the art world, being exhibited alongside Cohen’s own work to equal amounts of praise. Cohen says that AARON, like a true professional, even cleans its own brushes and cups.

Other people, such as Stephen Blessing of Carnegie Learning, say that AARON is creative, but only so far as Cohen himself is creative, having only programmed a duplicate of his own artistic thought process. Arguably, a zanelle-painting robot by any other artist would be inherently different based on its programmer, and not creative in itselfxiv. Placards at the Victoria and Albert Museum, for example, list only Harold Cohen as the artist/maker, with AARON’s contribution described under the ‘Materials and Techniques’ as “computer-generated drawing on paper”.

Pamela McCorduck coined the phrase “meta-artist” in describing Cohen, as he’ll more than often collaborate with AARON, by acting as a colorist, while letting the robot create the linework for the image.

Cohen’s own interpretation of creativity excludes AARON’s functioning: “It seems to me that creativity involves moving through a series of intermediate states that are significant to the degree that they are increasingly closer approximations to some weakly defined but strongly sensed further-off goal. The creative individual does not find those approximations, because they are not there to be found [in reference to Michaelangelo, who says that he sculpted by finding whatever was in the stone, and then chipping away whatever part wasn’t needed]; they don’t exist until he or she constructs them”.

What might happen, one wonders, if Cohen can code into AARON the artistic rules of another artist, and give AARON the choice as to which rules he uses and when, in much the same way that AARON already decides what goes into the paintings and when he is finished? Mixing Cohen’s rules of line art with Picasso’s rules of colour, for example, would result in a picture which is neither completely Cohen- or Picasso-inspired. Would AARON only be creative if he takes bits and pieces of multiple artists to create its own style, becoming completely novel and revolutionary? Cohen has taken many decades to explain to AARON his own style, and attempting to code in another artist’s rules may be a task that is better suited for a younger artist-programmer, but finding out the answer to that question might never be answered, as Cohen is notoriously protective of AARON’s programming (as any artist would and should be). However, for now, Cohen seems satisfied with AARON remaining his own personal project investigating art, computing, and creativity:

“Well, AARON could go on producing work indefinitely; the problem has always been that it would go on being the same work. Not the same individual image, but the same formulation which, by the way, is what most human artists do anyway, and they don’t do it for the next 200 years either… But to be realistic, I rather suspect that AARON will end when I end … why would anybody want to take up my other half?”

GHOST IN THE SHELL

Whichever interpretation of AARON you choose to believe, there is something truly remarkable about Harold Cohen’s work. AARON’s paintings, even if they duplicate the artistic rules of just one painter, are a marvel of both artistic dedication as well as programming know-how, and represent a perfect marriage between art and science.

For other essays by Harold Cohen regarding his robot AARON, visit: http://crca.ucsd.edu/~hcohen/

Tags: art, art robots, art theory