The summer is slowly coming to an end – sad but true! – and the National Gallery’s exhibit Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art has kept up a whirlwind of activity. On the final weekend that the exhibit is open, I urge everyone that hasn’t yet seen it to pay the National Gallery a visit, or to give it a second (I’ll be on my fifth!) look. I have been engaged with Sakahàn programming in various facets as an artist throughout the summer as panelist at the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) and Gallery 101, as a musician performing as part of the National Gallery’s Music in the Galleries series and for “Words and Music” at CUAG, and as a filmmaker documenting the Sakahàn Youth programming within the broader community.

I was first invited by the Carleton University Art Gallery (CUAG) to sit alongside Rebecca Belmore and Ursula Johnson on a panel moderated by curator Heather Anderson. The panel discussion was organized for the opening of Rebecca Belmore’s retrospective show at CUAG What Is Said And What Is Done (closing this Sunday, September 1), and Heather invited both Ursula and I as emerging/mid-career artists that deal with similar themes that arise in the work of Rebecca Belmore. The art gallery was at capacity, with overflow seating added, and I was pleased to see many new faces in the crowd.

The conversation that evening was highly illuminating for me, and remains with me weeks after the fact. Heather had the foresight to arrange a lunch meeting with the panelists the day prior so that we could all meet and discuss, and we quickly found some commonalities that were elaborated upon during the following evening’s discussions. A major focal point was language – Heather referenced some of my own writing about learning Anishinaabemowin, Rebecca’s extensive use of Anishinaabemowin titles in her earlier works, and Ursula’s fluency in her first language, Mi’kmawisimk (Mi’kmaq).

For me, the different approaches to Indigenous languages were striking and fascinating. Rebecca Belmore and I share common ancestry in Obishikokaang Wemitigoozhiiwitigwaaning; Lac Seul First Nation, Frenchman’s Head, an Anishinaabe (Ojibwe) community close to Sioux Lookout in Northwestern Ontario, Treaty #3 territory. Writing outside of the panel, I’ll take the opportunity to flatter Rebecca and her work – she has long been one of my biggest influences and inspirations for her brilliant cross-disciplinary artwork, fearless performances, critical approaches and unequivocally Anishinaabe perspective. Learning a few years back of our common roots in Obishikokaang deepened my appreciation of her work, and being invited to this panel was a tremendous honour and our first meeting.

With the commonalities in place – our differences. I am a generation younger than Rebecca; she is slightly younger than my mother, and the same age as my auntie. Their generation was one that saw tremendous upheaval for Indigenous peoples living within Canada. Rebecca tells of hearing her older relatives speak only in Anishinaabemowin, while she communicated only in English. My family, as many others, were adopted out of the community, severing our ties with the language. While moderating, Heather drew attention to Rebecca’s past use of Anishinaabemowin in the titling of her work, such as 1991’s Ayum-ee-awach Omaamaa-mowan: Speaking To Their Mother.

Image of Ayum-ee-awach Omaamaa-mowan: Speaking To Their Mother taken from Rebecca Belmore’s site.

In return, Rebecca noted that in more recent years, she has not followed her earlier Anishinaabemowin convention (see works in Sakahàn such as 2008’s Fringe), and admitted that she would be unable to read any of the text in the Saulteaux-Ojibwe New Testament displayed at the back of the room, part of the installation como in cielo cosi in terra (2006). For Rebecca, she said that her work is too time-consuming to devote additional time and resources to studying the Anishinaabemowin language, and she has within her circle of peers enough fluent speakers to translate anything that she needs.

Fringe (2008) by Rebecca Belmore. Photo © National Gallery of Canada.

With my peers, I’ve seen a shift in recent years in recognizing the urgency of preserving the Anishinaabemowin language. Without the immediate familial relations that speak the language, I’ve been left with the decision to either work hard to immerse myself in the language – thousands of kilometers away from my traditional territory, yet supported by a community of like-minded urban Anishinaabe neechies (friends), or to accept that the language is being lost. As an emerging artist, I have been working, much like Belmore did in her earlier works, to incorporate Anishinaabemowin into the titles of works and integrate the language into my English writing. This is a strategy which challenges accessibility, but also draws attention to the status of Indigenous languages, re-situating the words within a different context. The importance is alluded to within the title of the exhibit, Sakahàn. Named by local Algonquin Elder and artist Albert Dumont, the word means to “ignite a fire”, referencing the spiritual power of sacred fire, alluding to the Anishinaabe Eighth Fires prophecies, and signifying the Indigenous art scene which is already burning brightly.

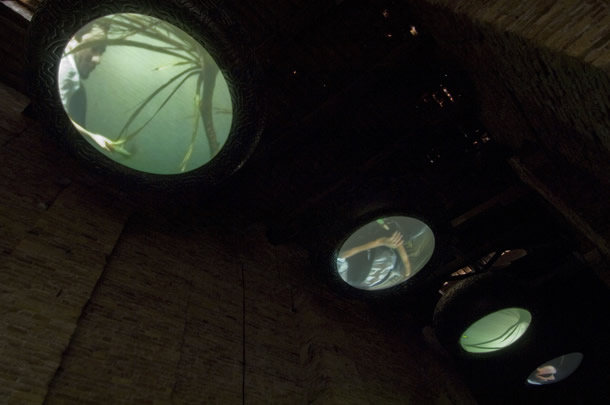

Aniwaniwa (2005) by Racheal Rakena and Brett Graham. Image from http://www.brettgraham.co.nz/work_installations_01.htm

One of the major curatorial themes for Sakahàn: International Indigenous Art is as the exhibition’s title states: situating artists by self-identified Indigeneity, rather than by regional or national boundaries. For me, this strategy has been crucial in identifying the commonality of Indigenous Peoples’ experiences of colonization. One of the most talked-about installations of Sakahàn (“the one with all the beds”), Brett Graham and Racheal Rakena’s installation Aniwaniwa (2007) immerses the viewer in a flooded Maori village in Aotearoa New Zealand. The residents of the village continue on with their daily activities, while set to a dreamy soundtrack by Maori musicians Whirimako Black, Deborah Wai Kapohe, and electronic musician Paddy Free.

The Horahora village along the Waikato River, where Graham’s father was born, was flooded in 1947 for the building of a hydroelectric dam. The description outside the installation states that this flooding places Maori identity in a state of flux, which “is reflective of the experience of many Indigenous peoples in the Pacific.” Viewing Aniwaniwa and Sakahàn within the context of the settler-colonial Canadian nation-state, I immediately was reminded of my own community’s history in Northwestern Ontario and that this is an issue that reaches far past the Pacific. Lac Seul First Nation was flooded without warning beginning in 1929 when Hydro Ontario constructed a dam at Ear Falls. The flooding turned the Kejick Bay community into an island, and displaced people from sites of cultural and historical significance.

70 years after the flooding of Lac Seul in 1929, a bridge was completed to Kejick Bay in 2009. Photo of bridge construction by Melody McKiver (2009).

Through Sakahàn, I had the pleasure of meeting and working with one of the Aniwaniwa artists, Brett Graham, on his repeat visits to Ottawa. Having seen Graham’s story in his artwork, myself and several other local Anishinaabe artists shared our community’s stories of flooding in Lac Seul and Lac de Mille Lacs First Nation, another Treaty #3 community in Northwestern Ontario which is located next to Rebecca Belmore’s hometown Upsala, Ontario. For me, this has been the unique power of Sakahàn – connecting local and visiting artists with the broader community, and sharing stories that are too often unheard. My final event in conjunction with Sakahàn will be as an animator on the Strangeness and Representation panel at Gallery 101 on Saturday August 31 between 1-5. On this final weekend of Sakahàn at the National Gallery, I hope that everyone takes the opportunity to visit some of the exhibits across Ottawa, and reflect on these stories. Chi-miigwech.

Tags: CUAG, Melody McKiver, National Gallery of Canada, NGC, Sakahan