Last week, I headed to Montréal for the 11th incarnation of the Elektra International Digital Arts Festival in Montréal. The five day event attracted artists and industry professionals from as far away as Dakar, Seoul, Istanbul and Shanghai, as well as various countries across Europe and North America, to the cosmopolitan Québeqois city, which is quickly, as many of us already knew, establishing a name for itself as THE creative hotbed for electronic arts. There was much to take in each day, and while it can’t all be discussed here, this post represents a compendium of the most interesting, evocative and stimulating experiences from my time there.

The Conferences

For those presenting at the International Marketplace for Digital Arts, the future, in the (wink) words of Chip Douglas, is very much now. The “professional rendez-vous” as it was dubbed by Elektra’s organizers, was a two-day blitz of presentations, debates and dialogues, given by over 30 international artists, producers, agents, broadcasters, curators, institutional directors and event organizers. While the format of the conference itself could be described as both a massive speed dating session and networking boot camp, leaving not quite enough space for attendees to fully digest all that was being offered, the conceptual framework of the event – arranged as a space to foster collaborations and to develop new, cross-border distribution networks, was clearly taken advantage of by all observers and presenters alike.

Some of the most thought-provoking presentations were given by organizations such as W2 (Vancouver), FAN et Centre Irisson (Casablanca), Trias Culture (Dakar) and Nabi Center (Seoul) who are each working, in a variety of ways, to increase the availability of technology – both open source software and physical hardware, access to media outlets, and opportunities to create multi-media art. Inspiring presentations were given by the organizers of the Zero One San Jose Biennial, Performa, and the Shanghai eARTS Festival, who showcased highly creative approaches to curating performance and electronic arts on a massive scale, while individuals like Nina Czegledy provided the group with stimulating philosophical and conceptual frameworks from which to consider larger topics such as new curatorial models for a digital age, whether social media can function independently as a voice for marginalized voices, and how artists might be able to use technology to (re)activate urban space or upset the proliferation of invasive technologies within the public sphere.

Key to many of the most appealing presentations was a sensitivity towards new social interactions and rituals developing as a result of technology’s pervasiveness in our daily lives, as well as a concern for keeping the media arts an open (read: free) platform for creativity. While it was unfortunate that there was not as much time for debate or discussion built into the two-days of programming, and that it may have, in hind sight, been a more successful event if the presentations were spaced out over a longer period of time, the IMDA was nevertheless a thought-provoking, if not motivating, portion of Elektra.

A/V performances

Of course, Elektra wouldn’t be Elektra without a massively spectacular display of immersive audio-visual performances by a selection of the world’s leading video, installation and electro-acoustic artists.

The kaleidoscopic, fully immersive Laser Sound Performance presented nightly at Usine C. by Edwin van der Heide was a true crowd pleaser, surrounding the packed crowd in pulses of pure prismatic colour set to waves of digital sound.

BEAT, a collaboration between Sylvain Pohu and Sixtrum was a surprising combination of rhythmic, intricate percussion composed to accompany a black and white video projection that contained a multitude of visual and text-based clips, surrounding the definition of the word “beat.” Switching continuously between the aural and social concepts of the word, with images ranging from those of instruments to factory workers to slaves, the performance at once called attention to its own physical construction while at the same time offering a form of cultural critique that was for the most part unique in comparison to many of the other A/V performances at the festival.

Treating the relationship between sound and light in a completely formal manner, ABCD-Light by Purform was a stunning series of geometric and linear visualizations of pulsating sounds – ultra-slick and impeccably-crafted without being arrogant; while both Herman Kolgen’s Inject V.02 and Dust demonstrated the incredibly detailed capabilities of high-definition video technology and, despite whether one may have found them clichéd in their narratives, were utterly gorgeous, overpoweringly sensual displays of eye-candy.

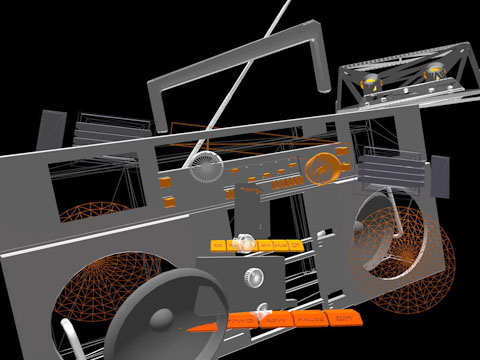

A favourite ultimately, had to be Cécile Babiole, Jean-Michel Dumas and Vincent Goudard’s quirky, playful and refreshingly humourous performance titled Donjon. Here, objects from everyday life – from domestic appliances to retro a/v equipment, racing cars to , were animated as very basic 3-D models, and as they bopped and bounced across the screen to the accompanying music, they were deconstructed, falling apart on themselves until they became no more than broken-down or flattened cross sections of their former selves. The minimalist, even old-school aesthetic of the video was paired with music reminiscent of arcade/video game soundtracks, giving the entire piece a wonderfully-nostalgic feel like only neon and break-beats can, all the while deconstructing the, as the artists call it, “glut” of consumer objects that surround us daily.

The Exhibitions

Many of the local artist-runs centres had partnered with Elektra to present digital, electronic or “new media”-based works.

While some, such as Ian Wojtowicz’s (US) The Betweeners– a series of portraits inspired by online profile pictures and digital visualization which attempted to map the virtual social connection of several Montréal strangers – or Ann Hirsch’s Scandalishious (both at Skol) took the digital world both as their media and subject matter, others, such as 216 prepared dc Motors by Zimoun at Galerie Push, and Pascal Dufaux’s Le cosmos dans lequel nous sommes, at Galerie Joyce Yahouda employed both simple and more complex electronic devices to create very different sculptural installations. Reminiscent of a futuristic tee-pee structure or the lunar-lander, Dufaux’s custom-made video-kinetic camera, used to take surveillance-inspired photographs while continuously rotating in hypocyclodoial motion around a series of mirrors, was almost more interesting than the images it had been built to capture, and like Zimoun’s sonic installation, presented the viewer with a truly hypnotic experience.

Further afield at Orobo, Kaffe Matthews presented a Québec incarnation of their Sonic Bed – a weighty wooden enclosure that houses speakers and a queen-sized mattress that is imbedded with subwoofers. Original digital tracks scored by Magali Babin, John Oswald and Georges Azzaria pulsed from the surround-sound system, while the subwoofers throbbed along to the beat, vibrating those who chose to lay in the bed into both meditative and rousing states.

Interactive in a completely different sense, Daan Roosegaarde’s Dune, installed on the upper level of Usine C, presented visitors to the festival’s main site with a field of luminous fibres that covered the concrete floor like a bed of tall grasses that flickered and blazed automatically, illuminating itself in response to noise and motion generated by people moving through the darkened hallway. Existing as a hybrid between the digital and natural world, Dune exemplified the poetic relationship that can exist between humans and technology, pointed most strikingly to the complexity, beauty and even fragility of this dialectic, and in a sense, perfectly encapsulated the spirit of Elektra .

Tags: Conferences, Elektra, Festival, Lasers, W2