The 15th edition of the Elektra Festival took place at the end of May. This year it combined with Mutek for their joint anniversary. During the festival Elektra hosts the International Digital Market Place which is a series of short presentations from international festivals, presentation centers and production spaces mixed with Canadian artists working with technology in some capacity. Artengine was invited to present, and we took this opportunity to describe the type of questions that drive the organization. Below is the text from our presentation.

Thank you for the invitation to present here at the Elektra/Mutek. It is almost always a pleasure to talk about Artengine to people. Well it’s mostly a pleasure for me. Let’s see how it goes for you.

Artengine is based in Ottawa, Canada’s capital but sometimes it just seems like distant and quaint suburb of Montreal….I think that might be all the context I will give you for now. We can move onto other things….

I thought it would be interesting to talk more about the ideas and questions that have driven our organization rather than the projects we have undertaken. I am hoping to present the activities and ideas of our organization as questionable, that is both open to question and perhaps somewhat suspect as well. One of the ways we hope to cultivate this openness at Artengine is to try and understand the organization itself as a project. The importance of this lies in how we understand our own narrative, particularly over the last few years as we have in many ways begun to deconstruct the organization itself.

As our funding and our festival project, Electric Fields grew we begun to question the notion of organizational growth, and what it meant to keep expanding in the way we had been. We began to ask ourselves, what was at stake in this process? And what specifically would it mean within the city that we are based? At the same time this was paralleled with a thinking about our social and political context and particularly bringing up questions about the notion of progress. While scientific and technological progress can be a wonderful thing, we are concerned that it can be infectious and blinding as well. If we believe ourselves to be a thoughtful and critical organization about technology, how do we position ourselves in relation to a belief in progress? If we are working inside the paradigm of progress how can we look backward without it being either reductive or nostalgic? If we are driven by the pace of technological development, caught up many times in the pursuit of the new and the now, how do we maintain or cultivate a different perspective of time?

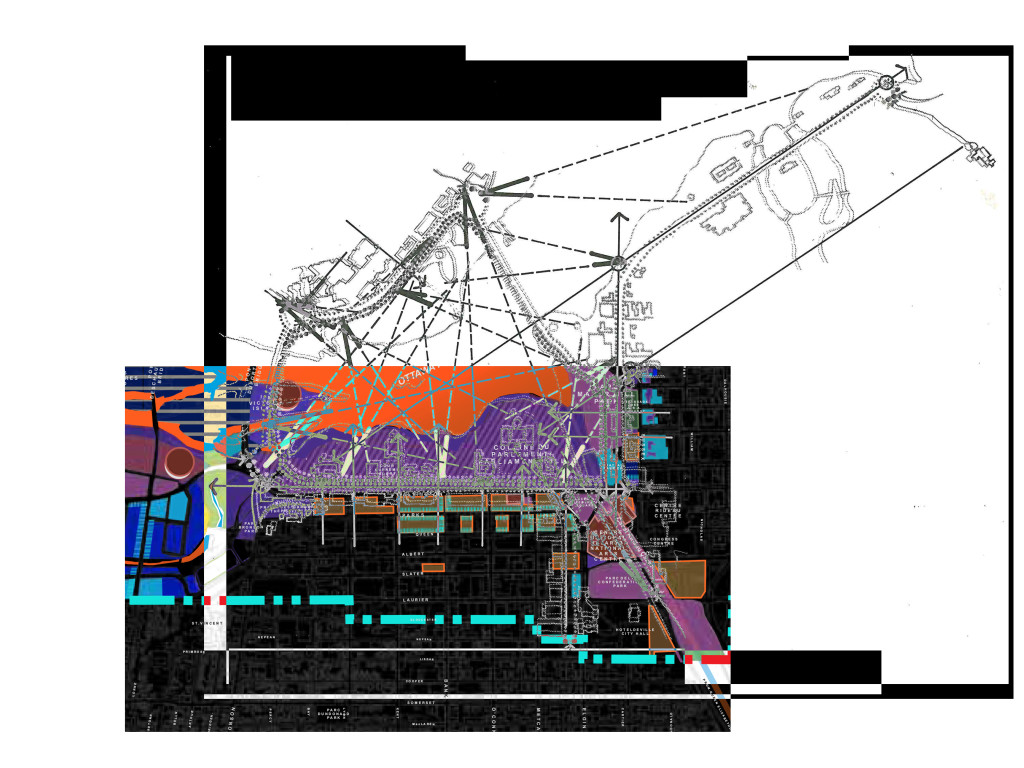

Since 2010 we have slowly deconstructed our festival project Electric Fields. We began to question the format and approaches as we sought different interdisciplinary collaborations until we had essentially turned the festival out into the city itself. We wanted to know what a festival would look like that was grown in the fabric of the city we are home in. How would it look different from a kind of festival that we thought it should be, and what role would the city play in defining or creating the festival.

The result was We Make The City! We Are The City! With this approach tried to push ourselves to engage in a more participatory approach from the art through to organization of the budget to the marketing. Despite the joy we found in this project our deconstruction continued. With an intensely collaborative project we found a friction arose between the time of the festival and the unpredictable time of collaboration.

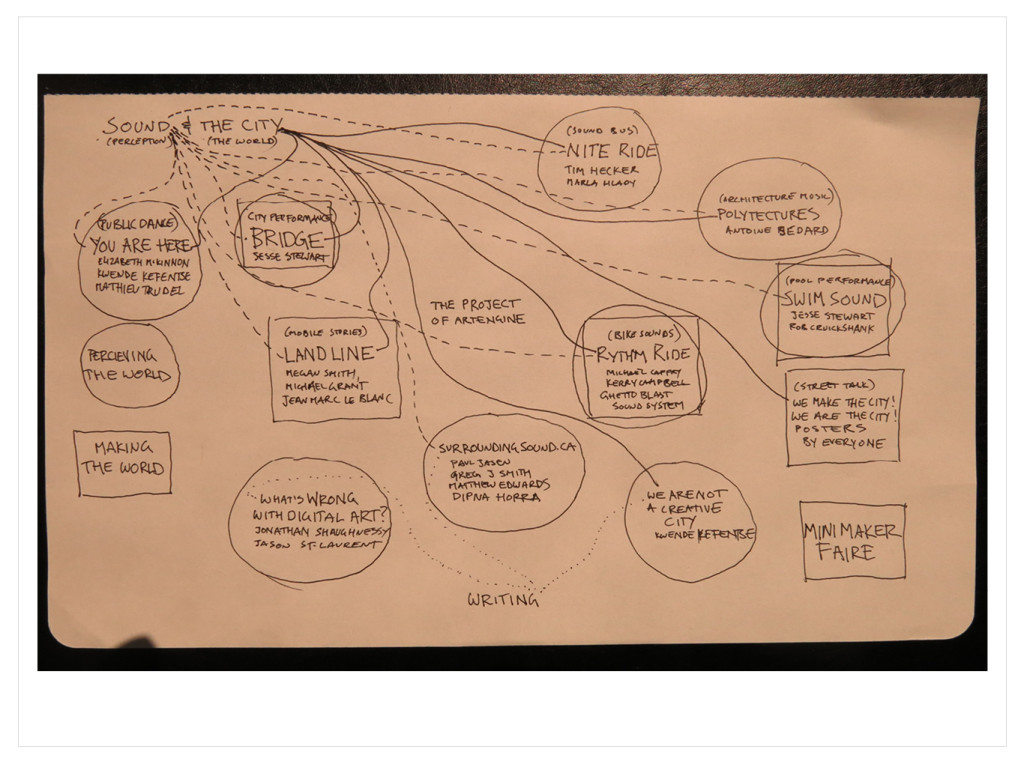

As I was trying to think through this for a presentation about what we do I drew this map. I was trying to sort out our projects and what they meant to us. What were they primarily about and how did they fit together over time. The first layer of connection lies between the ideas of sound and the city. They often overlap in our projects, but also exist separately. Underneath this I would describe two major and perhaps somewhat obvious themes – that of questioning or challenging how we perceive the world and that of the production of the world itself. What I found most interesting about looking at our projects in this way was how difficult it was to identify the line between the perception of the world and the production of reality. How much of a role do artist play in producing the world around us? and by extension how much responsibility do we have as a cultural organization to consider this?

This has lead us more recently to wonder about purpose and technology, particularly as we explore the area between design and art. Designs relationship with technology seems to us a conversation about purpose … to what end … what problem is to be solved… the conversation has the tone of a search for answers or at least a belief that answers are possible. One of the most exciting components of art is its embrace of purposelessness, but what happens when all of the embedded and integrated utility of technological tools dominate our creative practice? To this end perhaps we can imagine a program of entirely broken machines, not re-purposed or re-mastered, but non-functional possibly even wild and uncontrollable.

Should we ask ourselves how much comfort our productions and programming offer? How much support to an existing social and political structure do we provide? Or perhaps the inverse question, can we ask of our projects how much disruption or revolution or even democracy do they make possible? Even those projects that successfully create a mystique of discomfort or even terror provide this wrapped in the idea that the artist is in control or at least that the artist is in control of the machine…

In a slightly different vein, but not wholly unrelated writing has played an increasing role in the organization. Particularly as a strategy to cultivate thinking alongside doing so that writing plays into both the process of production and critical reflection. Of course writing then also becomes a project in and of itself often. One of most interesting written projects we undertook was a dialogue between myself and a city cultural worker and urban theorist Kwende Kefenste called We Are Not A Creative City. Our goal within this dialogue was to challenge the embrace of culture as valuable contributor to the economy, and while it might be true it seems that it would be much more interesting to embrace a narrative that cannot be defined in economic terms. With a four part series we tried to explore an alternate understanding of both the artist and the cultural practitioner in the making of a city.

If I could end by going back only a few years for us to a project that fits interestingly into the questions that we are raising for ourselves. Since 2008 we have collaborated with the Aboriginal trio A Tribe Called Red. The group has grown now to international success developing a kind of global phenomenon of what they called Pow Wow Step. However, they started with their long running club night Electric Pow Wow. This was their offering to redefine what it meant to be an urban indian, and we have worked with them as often as we can. In 2011 we commissioned them to rework some of their songs with singers for a live performance. The performance would as part of an Electric Pow Wow at what was then the Museum of Civilization in their grand hall. The grand hall is an incredible space designed by architect Douglas Cardinal (of Metis and Blackfoot descent) and houses reconstructions of six Pacific coast tribal dwellings. All this to say the layers of complexity in both colonization and decolonization are rich. What role do the tools themselves play in this process? In the process of continued colonization? In the empowerment of aboriginal peoples do decolonize themselves? Is this an important question?

You can see more of our projects on our programming page.

Tags: artengine, Electric Fields, Electric Pow Wow, Elektra, presentation, questions, Swim Sound