The best thing that Elektra had to offer was Kurt Hentschlager’s FEED—and they know it. It ran almost every night, sometimes twice in one night, and has been shown at five previous Elektra festivals. It is a work in two halves and the second half completely overshadows the first. So much so that until I came to write this I had almost forgotten about the first part: a projection of a featureless computer generated male body floating and replicating in a black void. Except for serving as a warning of how we might soon feel, I saw no real connection between this projection and what followed. And what followed was awesome.

I will never capture the experience in words. Every person I spoke to had a different impression. Before going in we all had to sign waiver forms acknowledging that we had read the warnings about how overwhelming the experience could be. No wonder the projection was so forgettable, we were all sitting there waiting for the pandemonium to begin. It was well worth the wait.

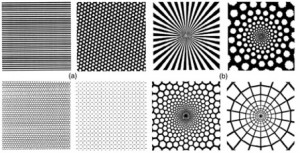

Theatrical fog flooded the room. I immediately began to assume that we are going to see something akin to a 1960‘s Expanded Cinema event, maybe with lasers if we were lucky. But the fog got so thick that the possibility of seeing anything was quickly ruled out. I couldn’t see my hand when it was right in front of my face nor could I tell if my eyes were open or closed. A strobe started up with accompanying pulsating sounds, and then the magic began. Rainbow colored vortexes and shimmering diagonal grids appeared, not in-front but inside my eyes. It was like an sober psychedelic experience. The scientists call these visions phosphenes. They are formed between the retina, as it is bombarded by light, and the visual cortex, as it strains to see something in the fog. You can approximate the FEED experience by pressing on your eyes or, of course, by taking hallucinogenics. Although it is more like the latter because you can always stop pressing your eyes at any moment and release yourself from the sensation. You can’t escape Feed. It is engulfing and can become quite claustrophobic.

Typical phosphene forms

At a few stages I had the urge to get up and move around, to feel untethered from three dimensional space like the faceless man in the prelude. Undoubtedly, that would be a heath and safety disaster. The bureaucratic mindset that had us signing liability release forms wouldn’t want us crashing into, vomiting over, or passing out on each other.

When the strobes began, I was quite relaxed; the rhythm created through light and sound was temperate. With hindsight, Hentschlager was just easing us into it. The intensity heightened. During the performance, I couldn’t help but recall a recent conversation about abs 카지노 and how similar techniques are used in these environments to captivate and engage the senses. Hentschlager was obviously aware of, and manipulating, a correlation between the frequencies he could generate and naturally occurring frequencies in the human body like heartbeats and brain waves. He was playing our senses like they were dials on a synthesizer.

Previous discussions of FEED, which has been shown around the world, talk about it as fusing the human and machine providing a vision of our cyborg future. I can’t help but channel Lev Manovich and Donna Harraway here and argue that Feed also provides a vision of our cyborg past and present. Renaissance perspectival machines harnessed and manipulated the properties of binocular vision. Cinema (and its various Victorian fairground precursors) works because our brains see movement when shown rapidly succeeding images. To be quite literal about it, all technology is just that – an extension and enhancement of human capabilities. We have been and always will be cyborgs.

Another Elektra work that operates on sensory deprivation and manipulation was Just Noticeable Difference (JND) by Chris Slater. Only one person can experience it at a time and I was one of the fortunate few. You crawl into a pitch black cube and lie down, as instructed, on your back. In the beginning I couldn’t work out if the faint buzzing in my ears was just tinnitus, induced by the night’s performances, or the work. I waited patiently. Then my stomach grumbled – or at least it felt like it did. Then my foot began to twitch and my breathing became bronchial. In sensory deprivation chambers it is common to become more aware of the sounds and movements of your body, so I wasn’t sure of the origin of these sensations.

Although, quickly the just noticeable difference became a very noticeable difference. I almost screamed. There was a tapping on my shoulder from underneath me and the ceiling of the space lit up with flashes of red. The space began to feel more like a coffin. Then came the thunder and lightning – a deep rumble with flashes of light from above. As the storm subsided I was turned into a human drum. The floor had morphed into something like a robotic massage chair switched to the ‘karate chop’ setting. The effect was no longer subtle. In the end it was more like being on a carnival ride.

My comparison with fairground experiences is not flippant. Fairgrounds and amusement parks were the sites where modern technologies of grand scale and spectacle were made available for the public to physically experience. They were theaters of machines; both generating technological wonders and reflecting the pervasive techno-culture. Their decline has left a gap. Where do we go now experience technologies beyond the cinematic? Where do we go to confront, externalize, escape and make sense of our media dominated habitat? I am not the first to suggest that contemporary art, museums, international art biennials and fairs have slipped into this terrain and become increasingly spectacular.

In the face of this, contemporary art criticism is scathing of the spectacular. Any display of impressive and enjoyable technology is seen as dangerous, homogenizing, distracting, isolating and pacifying. Critics invoke Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and Baudrillard’s Simulacrum and Simulation to express a suspicion of sensational affects. Any artwork using spectacular means and any viewer enjoying it are framed as critically unaware, or worse still complicit.

I am weary of criticism that assumes I and other viewers are easy dupes. Just because we sit passively, willingly absorbing, does not mean that our minds are not active. As Jacques Rancière argues “spectatorship is not a passivity that must be turned into activity. It is our normal situation. We learn and teach, we act and know, as spectators who link what they see with what they have seen and told, done and dreamed.” Through our interpretations we all actively construct meaning and knowledge. Then by communication with others we can transform the way a work of art is seen. Feed and JND definitely give us plenty to interpret. They offer experiences that we couldn’t otherwise know; an aestheticisation of senses and modes of perception beyond the dominant modes.

However, these works cannot elude the valid criticisms that, despite their content, spectacular works are in themselves spectacles of capital investment. They require a luxury of time, resources, funding and space to produce them. In their desirability and marketability they also marginalize less spectacular works, consuming everything from sponsorship to attention. Still highly contested, delving into these works is a roller-coaster ride of highs and lows.

______________________________

Here is a video that tries to capture Feed – but the camera doesn’t have a retina or visual cortex, so can’t really convey the experience: http://vimeo.com/403872

Texts by Lev Manovich’s can be accessed here: http://manovich.net/articles/

Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto, 1991 is here: http://www.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/Haraway/CyborgManifesto.html

Jacques Rancière ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ ArtForum, March, 2007 http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0268/is_7_45/ai_n24354915/

For more on the debate surrounding the spectaclular in contemporary art see: Rethinking Spectacle 31 March 2007 http://channel.tate.org.uk/channel

Tags: Chris Slater, Elektra, FEED, Just Noticable Difference (JND), Kurt Hentschlager