This weekend Artengine’s Artistic Director, Ryan Stec, is in Toronto for the launch of the book What is our Role? Artists in academia in the post-knowledge economy. The book is edited by Jaclyn Meloche, a recent PhD graduate from Concordia based in Ottawa until recently, and published by YYZ Books. YYZ and Jaclyn have organized a symposium on Saturday April 30th at the Toronto Public Library. We provide a preview of Ryan’s text, a kind of internal dialogue on the possibility of writing a manifesto in the 21st century. If you are in Toronto please join us! Or pick up the book from YYZ Books after the launch.

Can we write a contemporary manifesto?

The intellectual me tells the others in me that the manifesto is an artifact of modernity that is a doomed anachronism. [i]

The artist in me can see that the intellectuals have been the authors of their own demise.

The architect in me offers to build a new space for the writing of the anachronistic manifesto or its actionable items.

The intellectual voices his fear of manifestos and their flattening of the world. He is worried that the reduction of things can lead to dangerous simplification.

The artist believes the manifesto will unite us. He asks what of the condition of the now, of this moment…where can we meet? Where can we be together to speak, to discuss, to agree, to disagree, to build words and worlds together?

The intellectual wonders about the now of the digital commons and our supposed interconnectedness.

All three brood suspiciously.

The artist asks, can virtual public space only provide virtual interaction and virtual dialogue and virtual democracy? The intellectual responds that the virtual was once more associated with the virtuous and the essential before its association with something that only seems to be there.[ii] They wonder silently about the difference between the semblance of a thing and the thing itself.

The architect breaks the silence and offers to imagine a new space. He also offers to lead the project.

The intellectual asks to define the project.

The artist suggests a simple definition: to build a new intellectual commons together.

The architect knows the manifesto is the tool to unite.

The intellectual asserts that a contemporary manifesto would be too self-aware to assert a recognizable proposition.

The artist claims that radical change can only come from radical assertions… are you not affected?

The intellectual points to the reality of pluralism, of relativity, of specificity… will these not be causalities of any manifesto?

The architect asks if they can all admit that certain universals are worth believing as true?

The artist suggests that the contemporary manifesto will inevitably disagree with half of its premise, and proposes that its internal contradictions can be its strength.

The intellectual asks again for definition. What do we mean by contemporary? He suggests they turn to the Italian philosopher, Georgio Agamben.[iii] The artist resists the need for footnotes in a manifesto. The intellectual pushes on and proposes Agamben’s idea that to be contemporary is to be outside of one’s own time.

The artist argues there is no outside. It is a construction.

The architect asks if the artist has a problem with construction, and offers again to build. This time he proposes a division of some kind, one construction that will make two spaces, an inside and an outside from which to look upon the inside. The manifesto is a wall then. It divides out a section of the world to unify its malcontents.

The intellectual bristles at this binary division, and questions the need for more walls.

The architect suggests that it is very difficult to build shelters without walls.

The artist reflects on the idea of a manifesto as a form of shelter from uncertainty.

The intellectual asks if we can build uncertain walls as protection from certainty.

The architect suggests that perhaps the intellectual is finally getting into the spirit of the manifesto.

The artist asks if we have demonstrated sufficient self-awareness, and wonders if we can begin with the contemporary manifesto.

The intellectual is uncomfortable with how comfortable this feels.

The architect is uncomfortable because we haven’t begun to build yet.

And so we begin…

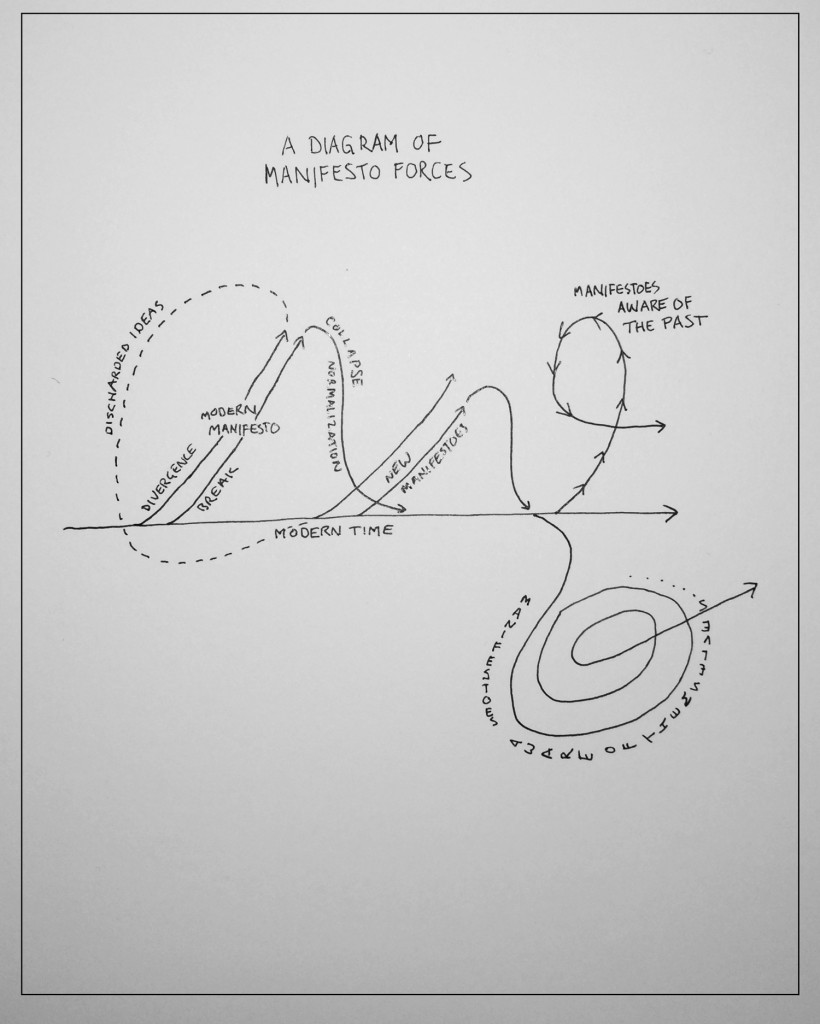

Diagram of manifesto forces, by Ryan Stec

We stake a claim on the condition of the present.[iv]

Our most beloved manifestos define the present in a way that we can grasp. The powerful manifestos of modernism appear as short, sharp, passionate shouts. They reduce reality to a simpler structure that we can perceive as a whole. They appear in magazines and little printed books. They sum up the world to just the right size so that action can be itemized and pinned to its door. The 21st century intellectual, however, is not built for the construction of a good manifesto. We traffic in complexity and rely on the belief that the world cannot be reduced to a form that could be handled by a public at large. We are the professional interpreters of the world through our instruments and technologies. From critical theory to quantum field theory, with the craft of language and the Large Hadron Collider, we believe that we reveal, if not truth, then at least truths in the plural. We have, in fact, multiplied truth and meaning. We fill books, libraries, server rooms and now data centres with a multiplication so staggering it is impossible to see what is happening in the world let alone what matters. Data centres are filled with these overwhelming and unstable truths, much of which is proprietary and armies of engineers seem unable to assess its structural integrity. It is not, however, the multiplication of truth which should be held responsible for its instability. Truth has always been unstable. The multiplicity of truth has been essential not for destabilization, but to reveal the inherent instability of truth.

This is the primary tenant of our claim to the condition of now – that the truth is, and always was, unstable.

This, then, is the challenge of our manifesto – to build it on unstable ground.

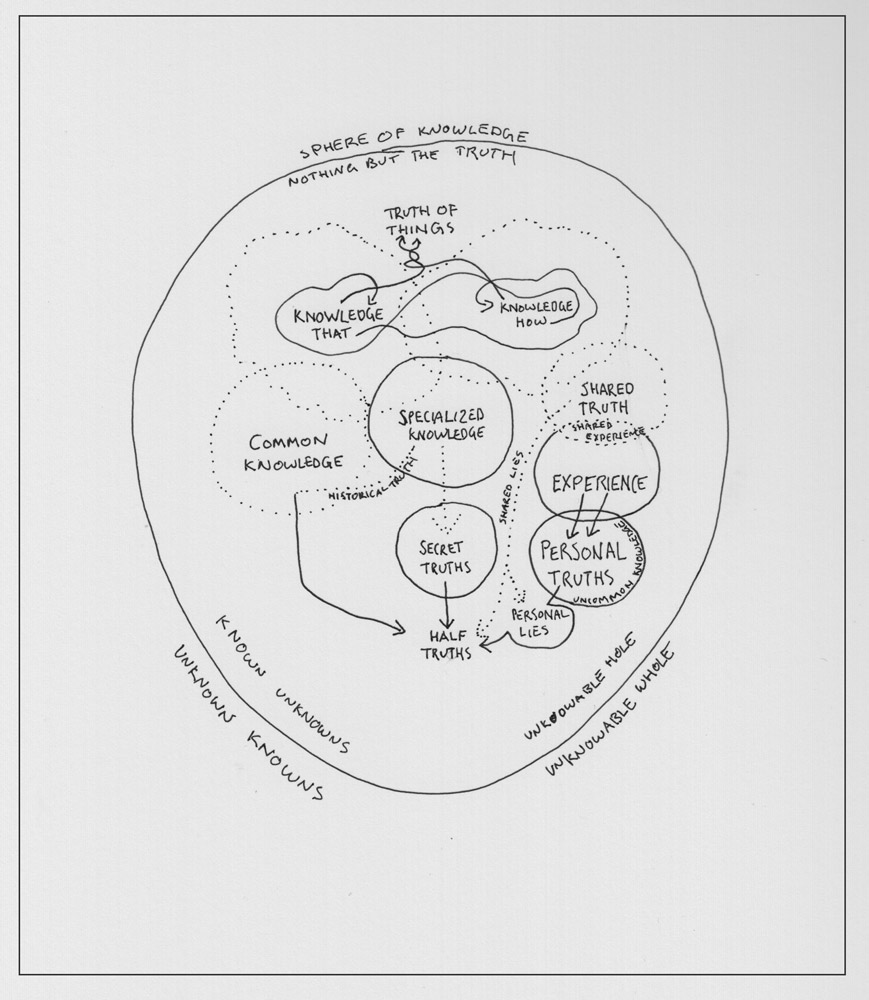

The intellectual interrupts and asks why we are using the word truth instead of knowledge?

The artist responds because its more evocative or perhaps more seductive.

The architect asks if the intellectual has a problem with truth?

The intellectual asks if they think the two are interchangeable?

The artist avoids the question and asks how interesting it would be to consider changing the task of knowledge production to the phrase – truth production?

The intellectual feels an uneasy association with Orwellian language.

This contradictory association with the word truth delights the artist.

The intellectual feels uncomfortable with the ambiguity.

The architect is thrilled by it.

Diagram of the sphere of knowledge (excluding unknown knowns), by Ryan Stec

Notes

[i] Martin Puchner argues in his book Poetry of the Revolution: Marx Manifestos and the Avant Gardes (2005) that the history of the manifesto is definitively framed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’ Communist Manifesto—that it is in that frame that the modern manifesto begins. He writes however that there is a pre-history of the manifesto and identifies two key moments in the seventeenth century that may be considered antecedents in the development of the modern manifesto. (Puchner 2005, 12-18) The first was the Puritan Revolution and in particular the ‘revolutionary theology’ of Thomas Münzer. The second was The Levellers and Diggers, two overlapping political movements from seventeenth century Britain. The Diggers where radical groups living communally and defending the notion of lands held in common for all people. The Diggers, and in particular Gerrard Winstanley, produced many significant and articulate tracts, proclamations, poems and songs including “A New Engagement, or, Manifesto” from 1648. Puchner suggests however, that despite the texts emerging from these two key moments being embraced retro-actively as manifestos by Karl Marx, Friedrich Engles, Ernst Bloch and Georg Lukàcs among others, the texts should be seen as only as proto-manifestos.

Janet Lyon however, in her book Manifestoes: Provocations of the Modern (1999) takes a more inclusive position. She connects texts dating back through to the 17th century as having continuity in form, style, content and title to the modern manifesto of the 20th century. For her The Diggers’ Song, the most well known song among the Digger poems, manifests and tracts, is one of the more significant radical proclamations prior to the French Revolution. (Lyon 1999, 16-23) The Diggers argued and sang out against emerging enclosure laws and the respective loss of the commons on the land, while also furthering the notion of the legitimacy and authority of a common people. For Lyon, the importance of the Diggers songs and texts is in the active incitement to collective resistance, but also in their efforts to ‘represent’ a group to itself.

The Diggers’ Song has a lively history winding its way through to twentieth century punk and folk music in America and the U.K. The song was recorded by the popular anarchist pop-punk group Chumbawumba on their album English Rebel Songs 1381–1984 (1988), while an imagined Digger Song was written in the 1970s under the title World Turned Upside Down by Leon Rosselson (recorded most by prominently by Billy Bragg in 1984). It is within this lineage of the Diggers and their song, echoing over the centuries, that this creative effort to explore the role of the artist and architect in academia is undertaken. The author and its audience certainly stand in a much more privileged position than the Diggers and Levellers, but this, The Contemporary Manifesto, hopes to nonetheless resist the banal anachronism of something like The Webinar Manifesto. It is with respect and admiration that it draws on this tradition of radical proclamations, and the attempt at a simultaneous call to action and a representation of ourselves to ourselves.

[ii] In the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), earlier and obsolete definitions of virtual refer to the particular qualities of a thing with a clear etymological relationship to virtue. (Oxford University Press 2016) In it’s second general category of definition it is the term essential that is placed in opposition to the actual. The OED identifies its earliest use in relation to the computer in 1959 to describe virtual memory, a technique that allows the secondary storage device to substitute for the physical memory. Its proliferation through computer science and into popular culture, perhaps most significantly through the term virtual reality, has created a fascinating tension between its roots as essence and its current use as simulation.

[iii] Georgio Agamben outlines his thinking on contemporariness in his short essay “What is the contemporary?” (2009) He elaborates several defining points of someone who is contemporary as being outside of one’s time, but also able to fix their gaze on it while not being “blinded by the lights of the century.” (Agamben 2009, 45) Agamben suggests that it is one’s anachronistic condition, which provides the productive space from which one sees one’s own time. “The contemporary is one who holds his gaze firmly on his own time so as to perceive not its light, but rather its darkness. All eras, for those who experience contemporariness, are obscure. The contemporary is precisely the person who knows how to see this obscurity, who is able to write by dipping his pen in the obscurity of the present.” (Agamben 2009, 44)

[iv] In Janet Lyon’s Manifestoes, the chapter “Manifestoes and Public Spheres” offers a rhetorical consideration of the term ‘we’ in the manifesto. (Lyon 1999, 23-26) She suggests that it is a division where a reader must choose to identify with the collective expression of the text and be part of the ‘we’, or choose an opposition, in which they become a ‘you’ and thus apart—not ‘us’ or ‘we’. The indeterminate or “… unspecified ‘we’ denotes and affords participation, on the part of its interpellated subject(s), in a provisional community whose power is located in a potentially infinite constituency.” (Lyon 1999, 26)

Works Cited

Agamben, Georgio. 2009. “What is the Contemporary?” In What is an apparatus? and other essays. (Stanford : Stanford University Press).

Conrad, Ulirch, ed. 1971. Programs and manifestoes on 20th-century architecture. (Cambridge : MIT Press).

Lyon, Janet. 1999. Manifestoes: Provocations of the Modern. (Ithaca : Cornell University Press).

Puchner, Marting. 2005. Poetry of the Revolution: Marx, Manifestos and the Avant Gardes. (New Jersey : Princeton University Press).

Tags: academia, intellectuals, manifestos, research, research creation