On Saturday 29 January, I attended a panel discussion held by the Ottawa Art Gallery in conjunction with the exhibition The Living Effect. The exhibition and the panel discussion were the result of the research, effort and connections of curator Caroline Seck Langill (although she wasn’t alone and the support of many others was mentioned).

A small caveat before I begin: This was only my second week in Ottawa. I had no idea I would be writing this for you and I did not turn up prepared. I admit wasn’t the most attentive listener at times. I sometimes let my mind wander a bit. I didn’t take notes. So the following account is inevitably patchy.

The premise of the panel discussion was humongous: art and science / technology. Such broad topical terrain seems to be a feature of discussions centered on more ‘fringe’ endeavors – new media art, as it is presently known, included. This is not to say the material presented was not engaging, it was just…wide ranging.

Three of the four advertised panelists spoke for 15-20 minutes about their practises, their perception of the intersection between art and science and technology, as well as the history and problems of new media art. Each presentation plotted a different tangent, with only occasional overlap.

Steve Daniels presented a wonderful little vignette by way of introduction to his former life as a scientist. We all ooohed appropriately as we zoomed in on colony of white pelicans.The colony is so populous their combined mass is visible on google earth, appearing to the untrained eye as a snow-capped point. Daniels spent numerous years studying these birds (was it 5?…7?…10 years? I can’t remember). But his burgeoning interest in the communication between individuals in the colony and his frustration with the limits of what science deems as knowledge, spurred him to flee the science scene in a hurry, with a vow never to return.

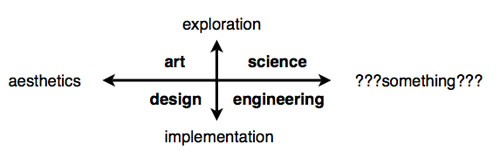

Now, time has passed and Daniels has revised his stance on the relationship of art and science. A diagram by Rich Gold, serves as a simple distillation of Daniels’ present perception of the interconnection of art, science, design and engineering. I wish I had taken a pen as I try to remember it for you:

Having come to reconcile both the artist and scientist within, Daniels has created his colony of light sensitive and communicative robots. A species somewhere between spider and a sea anemone, his creatures are rooted to the gallery wall. Their three spindly tendrils unfurl when you cast a shadow over them and they can communicate information about their encounters with their peers. Daniels encourages an anthropomorphic reading of his robots, as he explains how he programmed them to exhibit fear of visitors and their shadows. This loops around to Seck Langill’s quotation of Simon Penny in her curatorial text: “Why do we want our machines to appear alive?” For Daniels, he sees his project as an examination of communication, a sort of study in group behavior.

Steve Daniels, Sessile, 2008

Nell Tenhaaf provided us with historical insight through a discussion of a few works by of colleagues who have been experimenting with technology since the early 80’s. A group of names that would no doubt be familiar to those fluent in Candadian new media art. Only one name was familiar to me: David Rokeby, who’s iconic interactive sound installation Very Nervous System was on exhibition at the Carlton University Gallery at the same time.

Tenhaaf, provided us with nuggets of insight into her practice and the practices of her fellow compatriots who have enlisted the help of scientists and other miscellaneous geeks to create their work. She spoke of the slow evolution of a common language with her collaborator programmer Melanie Baljko and how useful it can be for artists to adopt and learn the jargon of scientists as a shortcut and bridge to this knowledge.

She also touched on a broader alignment of new media art: the way that a striving for novelty is a double edged sword; it propels exploration but also leads to pigeonholing by institutions. New media works are selected to help tick the box on media diversity and are never the subject of thorough or serious investigation by the history producing engines, galleries, critics, historians, museums…

Ryan Stec was the only panelist not an artist exhibiting in The Living Effect. He also pointed out to us that he was also the only non-academic/teacher on the panel. He approached the topic from his point of view as Artistic Director of artengine. His presentation was entitled ‘The problem of the prototype’ (or alliterated words to that effect) and he raised some of the issues around the intersection of the art world and those creatively exploring technology.

Stec pointed out that museums and galleries are often ill-equipped to display and conserve technology based work that often involves the customisation of tools and interfaces. He also posed the question where do we belong, us who experiment with technology stretching the creative boundaries of machines, formulas and processes? Perhaps the art world is not the place for us?

Many of his questions, I would argue, are similar to those posed by artists who feel external to the art mainstream, but are therefore, defined in relation or opposition to the mainstream. Looking back to the recent history of video art would dredge up similar problems and questioning. This type of work has been done by theorist Lev Manovich in his book The Language of New Media. Here he traces some of these historical patterns that digital media repeat in order to separate these from its developments.

Stec went on to speak of some exciting work being done in the circles he revolves in, where experimentation with tools and process is valued over products. One example he offered was a piece of software designed by GRL (Graffiti Research Labs). Their software was designed to enable public to create drawings that would then be projected onto the sides of large, public buildings. Stec was disappointed that this ‘democratising’ of media and the means of expression did not prevoke diverse or challenging statements from the public. Instead, most people, wrote their name or drew large penises.

Tenhaaf and Daniels suggested that one of the reasons behind a lack of quality engagement could be a problem they have seen with many new media works where the users have a limited understanding of the interface and it’s programming. They coined this the problem of expert verses novice users. Those who create or design a system or tool have an intimate working knowledge of its structure. Users approaching the system fresh may lack even some basic assumptions required to interact, or they will fall into repetitive or habitual forms of interaction. Although, abstracted out I would say that this divide between proficient and novice speakers of visual languages stretches across the entire art world.

Questions from the floor, as always is with these things, were thematic offshoots. One audience member posed the question of what queer technology would look like. Seck Langill responded that this was still fluid terrain and that Faculty of Art at OCAD University had just established a laboratory for LBGTQ students and teachers to explore this. Seck Langill posed a question for another of the exhibiting artists Marie-Jeanne Musiol who was present in the audience, asking about her experience of working with scientists on her photographs. Musiol expressed a dismay at the lack of interest expressed by scientists in her visual representations of their data. There was a tangled little question, the gist of which I think was somewhere along the lines of ‘It made sense to turn to artists to understand technology in the era of 80’s computer graphics, because this was a visual language. But, what business do artists have poking there noses further into science? The general consensus was that the door was opened to art and artistic exploration in the more applied and hybrid sciences. But that line between pure art and pure sciences is still very clearly defined.

Well. I’m surprised I was able to dredge even this much out of my memory. What I took away from the whole discussion was a sense that the course new media art is heading is both familiar and new. There is thar ever present need to validate the arts as a legitimate and valuable enterprise when compared to the sciences. Can it resist designs to use as a tool for social engineering or activism, in an age where web 2.0 is dominating our social and political lives? How can artists resist the mainstream, the museum, the market and still get recognition and a paycheck, especially in the age of digital reproduction? How can artists make their work more relevant to a wider public, particularly when they are extending the vocabulary of new media? These are all questions artists throughout the ages have struggled with, now with a digital spin.

For those wanting a more un-biased and complete record of the event check out the OAG website for a video recording of the discussion, soon to be posted.

Jaenine Parkinson

Tags: Conference, Curation, Electric Fields, The Ottawa Art Gallery, Thelivingeffect

Great post Jaenine! It’s a good debate. As an analogue photography geek, I’m always thinking about the developments in technology that both threaten and enhance this medium.

I feel lucky that there is such a strong movement growing to protect and promote film and instant photography, despite the overwhelming popularity of digital.