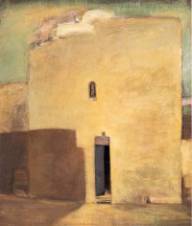

Jewish jeweler, Bni Sbih, Dra Valley,

Jewish jeweler, Bni Sbih, Dra Valley, Marc Eliany © all rights reserved

Abstract

Modern art historians suggested that there was hardly any art tradition in Morocco. Putting things in perspective, this article demonstrates that much artistic merit is found in Morocco’s material culture, many Western modern artists found artistic redemption in it and Moroccan Jews made a significant contribution to it in creation and diffusion.

Modern art historians may suggest that there was hardly any art tradition in Morocco. For in their eyes, Morocco was far from European influential art centers and much of the esthetic creation was not intended for artistic but utilitarian purposes. And yet much artistic merit is found in utilitarian objects that make Morocco’s material culture (Grammet, 1998).

The sense of esthetics is so omnipresent in Morocco that sensitive observers cannot discount it. It is present in structural and landscape architecture in urban centers such as Fez as well as remote villages high on the Atlas Mountains and further South deep in desert lands (Cherraddi, 1998). And it resurfaces in mosaics, sculpted surfaces (Grammet, 1998), stained-glass, illuminations of poetry and religious books as well as documents such as marriage contracts, tents (Sorber, 1998), carpets (Boely, 1998), curtains, bed covers, clothing (Sorber, 1998), musical instruments (Olsen, 1998), jewelry (Grammet, 1998), pottery (Martinez-Servier, 1998; Camps, 1961), ornaments of religious and secular values and much more…(Lovatt-Smith, 1995)

The sense of esthetics was (and remains) so pervasive in Morocco that it inebriated modern art pioneers such as Delacroix, Ferdinand Victor Eugene (1798-1863). Delacroix, a romantic painter, inspired by both classical and Medievial art, opened the gate to impressionism by introducing into European art the vivid colors of the Maghreb. Traveling in North Africa in 1832, he stopped in Tangier, Meknes and Algier. And moved by Jewish and Arab beauty, he produced masterpieces depicting the essence of Moroccan esthetics, including interiors of Jewish homes and portraits of Jewish women, which appeared in his eyes beautiful and charming and their costumes dignified and graceful. And so, observations of daily life in Morocco elevated Delacroix’s pictorial work to a classicism long lost in Europe. Following Delacroix, many artists, including Matisse, went on pilgrimages to Morocco, most searching for artistic redemption in the exotic, colorful and sensuous (Arama, 1991; Cowart et. al. 1990).

And the influence of Moroccan esthetics did not stop at the gates of the exotic. It inspired abstract contemporary art in the work of Le Corbusier and Kadinski, who evidently borrowed from Berber geometrical forms (Minges, 1996: 20-21). These geometrical forms found in architectural design, carpets, ceramics and jewelry, were often spontaneous bursts of artistic creativity among Moroccan creators. And their compositions remain astonishingly modern, clearly preceding the abstraction that became the foremost characteristic of modern art (Boely, 1998: 121 and Lehman, 1998).

Oral traditions convey persistently that Jewish life in Morocco goes back to Biblical times. Some say that artisans came to Morocco as early as 950 BCE during the reign of King Salomon, perhaps as his artisan emissaries and perhaps to escape his oppressive rule (see hints to Ethiopian migration in Roger, 1924). And successive waves of Hebrews immigration followed one another in conjunction with major historical population movements (i.e., with the Phoenicians or after the destruction of the First Temple) and displacements (i.e., Romans sold Jews as slaves all across the Empire). One way or another, Moroccan Jews believe that they laid the foundation to arts and crafts in Morocco since antiquity (Skounti, 1998; Chouraqui, 1985; Zafrani, 1983) and some research lends credence to this belief (Grammet, 1998; Camps, 1961; Elkhadem, 1998).

Jewish artistic expressions are evident in structural and landscape architecture, mosaic and pottery, sculpted surfaces on wood, clay and plaster, stained-glass, carpets, curtains, bed covers, clothing, embroidery, leatherwork, illuminations of poetry and religious books as well as documents such as marriage contracts, musical instruments, jewelry and metalwork, ornaments of religious and secular values and much more… All these may be considered as minor arts forms in Western lands but not so in Jewish and Muslim Morocco, where religion defined the meaning of life (Swarzenski, 1967).

But Jewish influence in the arts did not stop at the actual act of artistic expression in Morocco. Jews played an important role in commerce and international relations and thus were a principal vehicle of transmission of ideas relating to artistic tastes. They introduced Moroccan objects of artistic merit to foreigners and thereby had a significant influence on local demand and production of these objects. Jewish impact on artistic/esthetic tastes was not limited to bridging between Europe and Morocco but also between Morocco and Africa. For Jews dominated trans-Saharan commerce until the capture of Timbuktu by the French in 1894 (Grammet, 1998: p. 216).

It is common knowledge that Moroccan Jews dominated jewelry since centuries and metalwork (i.e., silver amulet, Hanukah lamps, copper trays) and some of their work was refined and exquisite in its artistic beauty (Grammet, 1998; Africanus, 1556). But less known is their leadership in gold and silver embroidery for secular uses (i.e., clothing for the Christian and Moroccan elite) and ceremonial uses (i.e., Torah mantle and wedding dresses) (Mann, 2000, Sorber 1998:182-183).

Jewish jeweler, Bni Sbih, Dra Valley,

Jewish jeweler, Bni Sbih, Dra Valley,

Jean Besancenot, 1934/39, Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris

Silver Amulet with star of David, private collection

Silver Amulet with star of David, private collection

Hanukah lamp, private collection

Hanukah lamp, private collection

Copper tray with star of David, private collection

Torah mantles, Beth El synagogue, Casablanca

Torah mantles, Beth El synagogue, Casablanca

Gold and silver embroidered wedding dress, Sale

Gold and silver embroidered wedding dress, Sale

Young woman in traditional wedding dress Jeune Jean Besancenot, 1934/39,

Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris

In the case of jewelry, some suggest that after the departure of Moroccan Jews, the quality of jewelry declined, especially in rural center of production and in many cases, rural jewelry production disappeared completely (Grammet, 1998). Some also suggest that a significant Spanish/Moorish influence is noticeable in Jewish Moroccan jewelry in terms of design and techniques due to the contribution of the Spanish/Portuguese refugees after the expulsion from Spain (Gonzales 1994, Flammant 1959).

It is common, for example, to find the Star of David in Moroccan jewelry (i.e., on Ahl Massa, Royal Museum of Central Africa, RMCA, Belgium) but Moroccan jewelry had very specific Jewish characteristics too. Headdresses of Jewish women in Southern Morocco were different from those of their neighbors due to edicts of hair concealment. In this particular case, head dresses consisted of colorful material (foulard) on which jewelry was set (Grammet, 1998: p. 336, i.e., Jewish women of Tahala of Besancenot, 1934/39, Institut du monde Arabe, Paris). In some cases, head dresses consisted of hair too (Morin-Barde, 1998: p.346).

Jewish women of Tahala of Besancenot, 1934/39,

Jewish women of Tahala of Besancenot, 1934/39,

Institut du monde Arabe, Paris

Synagogues tended to be modest on their outside but quite impressive inside. There were large glass vases set in metal ornaments (see memorial vase, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Eliany), illuminated manuscripts and amulets (see amulet, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Eliany), Torah mantle (Torah mantle, Ben Saadoun and Beth El synagogues, Eliany), Heichal curtains/cover (Ben Saadoun synagogue, Eliany). All these were well mentioned (i.e., Mann, 2000) but little was said about architectural elements and sculpted surfaces in synagogues and interiors of Jewish homes. Surely, Jews in Morocco shared much with their neighbors but there was enough to distinguish them too. For illustration purposes, the interior of the Ben Saadoun synagogue in Fes regroups elements that typify the finest of Jewish interiors in Morocco. Several of its walls and parts of its ceilings are made of sculpted plaster (interior, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Eliany) and a series of stained glass windows crown its upper ceiling (stained glass, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Eliany). In many cases, interiors were striking in their design sophistication in synagogues as well as in private homes (interior of Dahan synagogue in Fes, Eliany).

Torah mantle,

memorial vases

sculpted surfaces Ben Saadoun

Synagogue Fes, Morocco

Memorial vase, Ben Saadoun synagogue, 1992

Memorial vase, Ben Saadoun synagogue, 1992

Heichal curtains/cover Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Heichal curtains/cover Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Sculpted interior, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Sculpted interior, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Stained glass, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Stained glass, Ben Saadoun synagogue, Fes

Interior of Dahan synagogue in Fes

Interior of Dahan synagogue in Fes

Manuscript illumination was widespread in Morocco, especially in Coranic contexts but also in amulets used in popular rites (Elkhadem, 1998). In this sense, Moroccan Jews had much to share with their Moslem neighbors. But unlike their Moslem neighbors, much of the artistic creation in the form of illuminations of manuscripts and amulets disappeared or was destroyed.

Amulet, Ben Saadoun synagogue, 1992

Amulet, Ben Saadoun synagogue, 1992

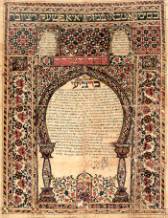

Jews illuminated marriage contracts (Meknes, Gross collection in Mann, 2000) and Passover Haggadoth most frequently. But occasionally, they also illuminated other Biblical passages, i.e., the Book of Esther which gained special significance following the 1492-1497 expulsion and conversion events in Spain and Portugal.

Illuminated marriage contracts, Meknes

Illuminated marriage contracts, Meknes

Similarly, Jews played a significant role in folk medicine, writing amulets to heal Jews and non-Jews or bring upon them blessings and good luck. For this purpose, Jews illuminated amulets on paper, leather, textiles, clay and other metals. Some of the amulets were small, designed for individual and private use but some were displayed for all to see in synagogues and private homes (Mann, 2000; see amulet, Ben Saadoun synagogue above, Eliany).

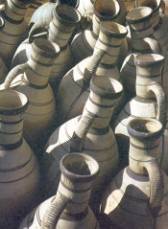

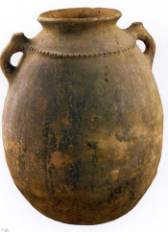

Jewish women made pottery to satisfy their basic needs for the most part but occasionally they did produce some for neighbors and friends and possibly for sale in neighboring markets (Decorative fruit tray and pottery in the market place, Eliany). Most of the pottery making was done from local clays using modeling techniques, without a potter’s wheel. Deriving clay from a riverbank and fashioning it was associated with the act of creation and was often considered a sacred act of a mythical dimension (Martinez-Servier, 1998).

Decorative fruit tray, Ouarzazat

Decorative fruit tray, Ouarzazat

Pottery in the market place, Sale

Pottery in the market place, Sale

Jewish men were rarely involved in pottery making but it is not inconceivable that there were Jewish potters at one time or another. Men in Morocco often used potters wheels and according to some, Phoenicians introduced local inhabitants to it (Camps, 1961). It is also very likely that men sculpted stones, although it is rarely mentioned in art reviews.

Forms and decoration of Moroccan pottery and sculpted stone are loaded with meanings and symbolism, which according to some go back to prehistoric periods and may have special significance to archeological research (Martinez-Servier, 1998). Some of the symbols and decoration found on Moroccan pottery have been associated with Nabathian writing (Elkhadem, 1998). Some oil lamps, for example, resemble ancient Hebrew lamps and their forms may date back to Biblical/Roman times (i.e., ancient oil lamps sculpted in stone, private collection, Eliany). Decorations may be painted (butter pot, Batha museum, Fes), engraved (engraved plate, private collection, Eliany) or sculpted on a pottery surface (RMCA, Belgium).

Art reviewers tend to emphasize utilitarian use to diminish artistic merit (i.e., oil lamps) while artistic merit is understated or ignored in cases where utilitarian use was not intended, i.e., stone sculpting (for example: Man and Wife and warrior, below).

Ancient ceramic oil lamp, private collection

Ancient ceramic oil lamp, private collection

Ancient stone sculpted Hanukah lamp, private collection

Ancient stone sculpted Hanukah lamp, private collection

Ancient stone sculpted Shabbat lamp, private collection

Ancient stone sculpted Shabbat lamp, private collection

Ceramic butter shop, Batha museum, Fes

Ceramic butter shop, Batha museum, Fes

Engraved ceramic plate, private collection

Engraved ceramic plate, private collection

Pottery with sculpted surface RMCA

Pottery with sculpted surface RMCA

Stone sculpted man and wife,

private collection

Stone sculpted man and wife,

private collection  Stone sculpted warrior, private collection

Stone sculpted warrior, private collection

Given the overpowering traditional cultural setting which provided the context for the artistic expression of Moroccan Jews, it is interesting to explore how and when the Moroccan Jewry wandered into contemporary form of art.

It is clear that in spite of the encounter with visiting artists such as Delacroix, Western art left little impression on Moroccan artists, probably because the world of meanings of Moroccan Jews remained bound by religious constraints. In this sense, a significant breach had to occur in Morocco for artistic creation per se to detach itself from artistic creation in its craft form. Given the strongly grounded traditional patterns of artistic creation in Morocco, an artist had to deviate from them to break ground into modern and contemporary art forms. But until the early 50’s, religious and traditional constraints remained potent and only sustained exposure to external cultures, i.e., French, Israeli or North American, made contemporary artistic expressions legitimate.

In this context, contemporary art expressions have gained ground in Morocco even if they did not detach themselves completely from the world of colors and symbolism in which they were born and which served a fertilization ground to Modern artists from Delacroix through Matisse and Kadinski. As Moroccan painters broke grounds into contemporary art forms of expression, they found themselves on a perennial crossroad, the crossroad where North and South or East and West met since many centuries.

The exposure to French art centers is noticeable in the work of Elbaz and BenHaim.

Leading among contemporary Jewish artists in Morocco is Andre Elbaz, born in El Jadida (Mazagan), in 1934. He studied art and theatre in Rabat (1950-55) as well as in Paris (1957-61) and taught art in Casablanca (1962-63).

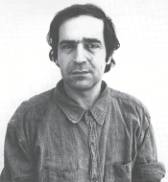

André Elbaz in his studio

André Elbaz in his studio

His work depicts Jewish themes in the abstract expressionist tradition: i.e., figures in synagogue settings, tragic events such as the Holocaust (exhibited at Yad Vashem in 1985) and the Inquisition in 1992.

Gouache on paper, André Elbaz

Gouache on paper, André Elbaz

Living in Paris, his most recent work vacillates between expressionistic portrayals of Jerusalem and powerful conceptual abstract work in which he yearns to eradicate interfaith destructiveness.

Untitled, André Elbaz, colored paper paste, 1987

Untitled, André Elbaz, colored paper paste, 1987

Maxime Ben Haim born in Meknes in 1941, studied art in Paris in the mid sixties, lives in Montreal since 1979.

Maxime Ben Haim self portrait, acrylics on paper

Maxime Ben Haim self portrait, acrylics on paper

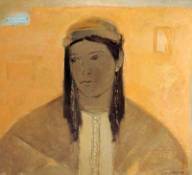

Ben Haim elevates Moroccan the Jewish quarter (Melah) as well as ancestral figures from common existence to archetypal transcendence in a somewhat expressionistic/realistic style.

Miriam, 1988, Acrylics and oil on paper, 61x56 cm.

Miriam, 1988, Acrylics and oil on paper, 61x56 cm.

House in a shadow, 1988

House in a shadow, 1988

Acrylics and oil on canvas, 109x130cm,

Ben Haim’s work is firmly grounded in Jewish roots and yet it transcends cultural boundaries, bridging across collective memories binding Jews and Arabs across many generations.

Pinhas Cohen Gan born in Meknes in 1942 in Meknes, immigrated to Israel in 1949, graduating from Bezalel Art Academy (1970), the Hebrew University (1973) and Columbia University in 1977.

Pinhas Cohen Gan, photo of Liora Laor

Pinhas Cohen Gan, photo of Liora Laor

Latent figurative circuit, 1977,

Latent figurative circuit, 1977,

Acrylic and oil on a sheet and a cardboard

30x32x218 cm.

Pinhas Cohen Gan is well known as a conceptual abstract painter in Israel. Cohen Gan juxtaposed the individual and his environment, confronting men to “scientific” realities, a metaphor for the alienation of newcomers from Arab countries in a ‘Westernized’ Israel (Fuhrer 1998; Omer 1983).

Marc Eliany, born in 1948 in Beni Melal, immigrated to Israel in 1961 and moved to Canada in 1976. He was educated at the Technion (1969-71), the Hebrew University (1971-76) and Carleton and Ottawa Universities (1976-1981).

Eliany in his studio, Photo of Camille Zakharia,

Eliany in his studio, Photo of Camille Zakharia,

Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Canada

Eliany is a multidisciplinary artist dedicated to documenting Jewish life in Morocco. He addresses issues relating to inter-cultural tolerance in a symbolic expressionist fashion.

Man at work, 1977, Gouache on cardboard, 50x70cm

Man at work, 1977, Gouache on cardboard, 50x70cm

After the market on a bright sunny day, 1994

After the market on a bright sunny day, 1994

Acrylics and oil on canvas board, 50x60 cm

"Eliany touches the heroic, the power of the symbol… His painting reduces rhythms to their essential… His work expresses his deep and colorful spirituality, and his fierce sensuality…” (Ouaknine, 1994).

From an historical perspective, much artistic merit is found in Morocco’s material culture in the work of common artisans and craftsmen. Western modern artists found artistic redemption in it and Moroccan Jews made a significant contribution to it in creation and diffusion. Given the strongly grounded traditional patterns of artistic creation in Morocco, artists had to deviate from them to break ground into modern and contemporary art forms. But until the early 50’s, religious and traditional constraints remained potent and only sustained exposure to external cultures, i.e., French, Israeli or North American, made contemporary artistic expressions legitimate. There are certainly many more artists to represent Moroccan Jewish artistic creation and in due time, more will be written about them. Meanwhile, the four selected here, Elbaz and BenHaim on one side and Cohen-Gan and Eliany, on the other side, certainly typify the breakthrough into contemporary art, forgetting not their roots.

Africanus, Leo, 1556 Description de l’Afrique, Lyons

Arama, Maurice, 1991 Itineraires Marocains, Jaguar, Paris

Boely, Gérard, 1998 Les Tapis du Moyen Atlas dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Camps, G. 1961 Monuments et rites funeraires protohistoriques

Arts et Métiers graphiques, Paris

Cherraddi, Cadre, 1998 Les Kasbah du Sud dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Chouraqui, André, 1985 Histoire des Juifs en Afrique du Nord, Hachette, Paris

Cowart et al. 1990 Matisse in Morocco 1912-1913

National Gallery of Art, Washington

Elkhadem, Hossam, 1998 Les Manuscrits dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Flammant, P., 1959 Les communautes Israelites du Sud-Marocain,

Imprimerie reunites, Casablanca

Fuhrer, Ronald, 1998 Israeli Painting,

An Elephant Eye Book, New York

Gonzales, V., 1994 Emaux d’Al Andalus et du Maghreb,

Edisud, Aix en Provence

Grammet, Ivo, 1998 L’esthetique de la culture materielle dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Grammet, Ivo, 1998 Les tapis du Haouz dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Grammet, Ivo, 1998 Les bijoux dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Grammet, Ivo, 1998 Eléments d’ architecture et mobilier en bois dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Lehman, Zineb, 1998 Le Tapi Ouaouzguite dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Lovatt-Smith, Lisa, 1995 Moroccan Interiors, Taschen, NewYork

Mann, Vivian B., 2000 Morocco, Jews and Art in a Muslim Land,

Merrel and the Jewish Museum of New York, New York

Martinez-Servier N. 1998 La poterie dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Minges, K., 1996 Berber Teppiche und Keramik. Museum Bellerive, Zurich

Morin-Barde, Mireille, 1998 Coiffures, maquillages et tatouages dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Olsen, Rovsing, M., 1998 Traditions Musicales de la Montagne dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Omer, Mordechai, 1983 Pinhas Cohen Gan 1983

Haifa Museum of Modern Art, Israel

Ouaknine, Serge, 1994 Gates of Welcome, Auberge des Arts Virtual Publications, Canada

Roger, R. 1924 Le Maroc chez les auteurs anciens, Les Belles Lettres, Paris

Skounti, Ahmed, 1998 Introduction Historique dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Sorber, Frieda, 1998 La tente dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Sorber, Frieda, 1998 Technologie dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Sorber, Frieda, 1998 Les textiles d’ameublement dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren

Sorber, Frieda, 1998 Les vetements dans Splendeurs du Maroc, Musee Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Tervuren (pp.182-183).

Swarzenski, Hanns, 1967 Monuments of Romanesque Art, Chicago University Press, Chicago

Zafrani, Haim, 1983 Milles ans de vie juive au Maroc. Maisonneuve et Larosse, Paris

Other sources:

Andre Elbaz, 1971 Seuls

Andre Elbaz, 1991 Of Fire and Exile